Keywords: dyslexia, definitions of dyslexia, cultural relativism, safeguarding

Dyslexia knows no barriers. At least, this is what we are often led to believe. It knows no borders, it knows no countries, and it knows no race. Dyslexia is neurological, dyslexia is hereditary, dyslexia is human. Dyslexia is neither political nor religious. Dyslexia is ethnically neutral. Dyslexia is not “word blind”, it is colour blind – or so we would like to think. But is this view actually backed up by evidence?

The truth of the matter is that “what dyslexia is” depends on “where dyslexia is”. Around the world, dyslexia is both measured and defined differently, and this means that the definitions used will be contingent upon which body assumes (or is assumed to have) the authority to define it.

This piece will comprise a review of the current definitions of dyslexia, coupled with a commentary on why this is problematic. Let us begin with the review.

I. Review

I shall begin with a basic claim: that there is no single definition of dyslexia. In itself, this claim may be both unsurprising and, prima facie, uninteresting. However, I intend to show that it is anything but uninteresting, and may have far reaching consequences.

In order to show the many definitions of dyslexia, I shall simply list a broad selection of them. This will be done in alphabetical order of nationality or national grouping.

Arab States

As cited in Al-Odaib and Al-Sedairy, the King Salman Center for Disability Research concludes first, that dyslexic subjects are characterized by “incompetence” in many behavioural characteristics and basic reading skills “compared with their ordinary peers”; and second, that dyslexic subjects “suffer from clear incompetence” in auditory perception, word analysis, word meaning, sentence comprehension, paragraph, and text understanding “compared with their ordinary peers” (Al-Odaib & Al-Sedairy, 2014).

Australia

The Australian Government’s Disability Standards Education document (2005), Dyslexia is a “persistent difficulty with reading and spelling

”.¹

Canada

Dyslexia Canada describes²

dyslexia as a “specific learning disability in reading”.

Denmark

According to the Dyslexia Association of Denmark,³

dyslexia is a “congenital and invisible challenge that makes reading and writing difficult”. It is also described as a permanent disability, experienced as a handicap.

Europe

According to the European Dyslexia Association (EDA), dyslexia is “used as a term for a disorder that is mainly characterized by severe difficulties in acquiring reading, spelling and writing skills”.⁴

France

The French national dyslexia support organisation, APEDYS⁵

, defines dyslexia as ‘ a specific disorder whose deficit area must be treated effectively and early in order to highlight the intact, sometimes superior, qualities of this "extra-ordinary" brain”.

Germany

The German Bundesverband Legasthenie (BVL)⁶

refers to dyslexia as a “circumscribed (umschriebene) reading and spelling disorder” [involving] clear weaknesses in the area of reading and spelling which can NOT be attributed to developmental age, below average intelligence, lack of schooling, mental illness, or brain damage.

Hungary

The Dyslexia Association of Hungary

⁷ states that “the first and most important symptom of the development of dyslexia is the mixing up of letters. The most frequent being the mixing up of b-d”.

India

The Dyslexia Association of India states

⁸

that dyslexia is “a Neurological Condition that is characterized by difficulties that mainly affect the ability of a child to read, write and spell”. It goes on to say that often, “weaknesses may be seen in areas such as language development, memory and sequencing”, and often manifests in problems in “listening, thinking [and] speaking”.

The Maharashtra Dyslexia Association calls it “a specific learning difficulty which affects a person's ability to read, spell and understand language that he / she hears, or express himself / herself clearly while speaking or in writing”. They make it clear that it “is not a disease [and] it has no cure. Dyslexia is caused by abnormalities in the way information is processed in a brain which is often gifted and productive in many other areas”. ⁹

Ireland

The Dyslexia Association of Ireland

¹⁰

explains that dyslexia is a “learning difference that can cause difficulties with learning and work”. Everyone with dyslexia is different, “but there is a commonality of difficulties with reading, spelling and writing and related cognitive / processing difficulties. Dyslexia is not a general difficulty with learning, it impacts specific skill areas”. They point out that it is a recognised disability under Irish law.

Japan

The Japan Dyslexia Society NPO Edge

¹¹

gives the following information: the word dyslexia is purely used in Japan for acquired dyslexia as a medical term. As an educational term, LD (Learning Disorder) is more widely used. It then explains that reading, writing and calculation difficulties are listed as Learning Disorders but are rarely diagnosed as such in medical institutions as there are no clear diagnostic criteria.¹²

Kenya

Dyslexia Kenya gives a definition¹³ that dyslexia is a specific learning difficulty that makes it difficult for people to read, write and / or spell. It is a language-based hidden learning difficulty that mainly affects the development of literacy and language-related skills and is characterized by difficulties with working memory, processing speed, accurate and / or fluent word recognition, and the automatic development of certain skills that may not match up to the dyslexic individual’s other cognitive abilities.

Nigeria

The Dyslexia Foundation of Nigeria¹⁴ states that dyslexia is “a learning challenge that is language-based. The term ‘dyslexia’ can refer to a multitude of symptoms that result in difficulties with language skills, such as spelling, reading, comprehension, and pronouncing words”.

Romania

The Bucharest Association for Dyslexic Children defines¹⁵ dyslexia as a neuro-biological dysfunction that affects the development of the ability to read.

Russia

There is no single definition of dyslexia in the Russian Federation; however, the current definition of dyslexia, as used in the leading Russian textbook on speech and language disorders, states that dyslexia is “a partial specific impairment of the process of reading, which is caused by the immaturity of higher mental functions and is manifested in repeated consistent errors”.¹⁶

Singapore

The Dyslexia Association of Singapore notes¹⁷ that it is guided in its definition of dyslexia by the Singapore Ministry of Education. They define dyslexia as a type of specific learning difficulty identifiable as a developmental difficulty of language learning and cognition, primarily affecting the skills involved in accurate and fluent word reading and spelling. Characteristic features of dyslexia, they state, are difficulties in phonological awareness, verbal memory and processing speed.

Turkey

(Kargin & Guldenoglu, 2016) and Birkan (2016) show an understanding in Turkey of "disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding or in using language, spoken or written, which […] may manifest itself in imperfect ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell, or do mathematical calculations."

The United Kingdom

There are several definitions used in the United Kingdom. Influential in education circles is the 2009 report by the late Sir Jim Rose, which describes dyslexia as “difficulties in phonological awareness, verbal memory and verbal processing speed” (Rose, 2009). The British Dyslexia Association talks about it as a learning difference which primarily affects reading and writing skills, but which does not only affect these skills. It goes on to say that dyslexia is actually about how the brain processes information. ¹⁸In 1999 the British Psychological Society proposed a definition which read that "Dyslexia is evident when accurate and fluent word reading and/or spelling develops very incompletely or with great difficulty". ¹⁹Since then, there have been other proposed definitions and understandings mooted on their website.²⁰

The United States

US Public Law (115-391)²¹ says that “The term ‘dyslexia’ means an unexpected difficulty in reading for an individual who has the intelligence to be a much better reader”, while the International Dyslexia Association²² says that it is a “specific learning disability that is neurobiological in origin […] characterized by difficulties with accurate and / or fluent word recognition and by poor spelling and decoding abilities. Secondary consequences may include problems in reading comprehension and reduced reading experience”. DSM-5, authored by the American Psychiatric Association, says that dyslexia may be seen in terms of difficulties in accuracy or fluency of reading which are inconsistent with a person’s chronological age, educational opportunities or intellectual abilities, and which, without accommodations, will significantly interfere with a subject’s academic achievement.²³

The American Dyslexia Association talks²⁴ of “gene-conditional assessments transmitted by inheritance in humans. The sensory perceptions are affected by genetic processes in the brain”. The US National Center on Improving Literacy attempts to correlate a number of US and international definitions, concluding in its document “Commonalities Across Definitions of Dyslexia”²⁵ that dyslexia is a “brain-based disorder” that is frequently associated with “difficulties in phonological processing, cognitive processing, or both”, and that it is related to “unexpected difficulties” in foundational skills such as reading.

UNESCO

Finally here, and interestingly, UNESCO²⁶ states that a good way to understand dyslexia is to establish “what it is not. It is not a sign of low intelligence or laziness. It is also not due to poor vision. Dyslexia is a common condition that affects the way the brain processes written and spoken language”.

II. Commentary

What we see clearly is that there are as many definitions of dyslexia as there are organisations defining it. We may also assume that without any single, universally-accepted umbrella organisation, we have no organisation-transcending standard, no Archimedean point as it were, against which to judge which of the differing definitions are better. After all, who is to judge how we even understand the notion of better, with so many competing cultural and professional demands making their voices heard? A definition that works for a clinical psychologist might not work for a primary school teacher; a definition that words for a primary school teacher might not work for a campaigning organisation. A definition that works for a campaigning organisation in one culture may not work for a similarly-positioned organisation in a different culture. Which profession, we might ask, and which culture, is the right one?

Without a culturally-neutral standard against which our different definitions can be judged, we are left searching for culturally-contingent ones. And without a culturally-neutral standard of which culturally-contingent definitions we have are better than all the others, we risk being left floating in a sea of “dyslexia relativism”. Any dyslexia definition might be accepted as being as good as any other.

To illustrate this point, I’ll turn briefly to the work of philosopher Paul Boghossian, who in his paper Fear of Knowledge set out the basic conditions of a relativistic worldview (Boghossian, 2007). We shall go through it here in a point-by-point manner:

1. There are no absolute facts which can confirm or disconfirm particular judgements.

(I will call this Boghossian’s first thesis, of non-absolutism).

2. We must not construe utterances of the form

'such-and-such is true'

as expressing the claim

such-and-such is true

but rather as expressing the claim:

according to the framework that I accept, such-and-such is true

(I will call this Boghossian’s second thesis, of relationism).

3. There are many alternative frameworks (indeed, a potentially infinite number), but no facts by virtue of which one of them is more correct than any of the others.

(I will call this Boghossian’s third thesis, of pluralism).

Now let’s apply this to our many definitions of dyslexia.

1. There are no absolute facts which can confirm or disconfirm that one or another definition of dyslexia is the correct one.

(from Boghossian’s first thesis, of non-absolutism).

2. We must not construe utterances of the form

'dyslexia is about difficulties in phonological awareness, verbal memory and verbal processing speed'

as expressing the claim

dyslexia is about difficulties in phonological awareness, verbal memory and verbal processing speed

but rather as expressing the claim:

according to the framework that I accept, dyslexia is about difficulties in phonological awareness, verbal memory and verbal processing speed

(from Boghossian’s second thesis, of relationism).

3. There are many alternative frameworks (indeed, a potentially infinite number), but no facts by virtue of which one of them is more correct than any of the others.

(Boghossian’s third thesis, of pluralism).

There are, therefore, no facts by virtue of which the claims made within these many frameworks is more correct that any other.

In the face of so many definitions and no neutral standard, there appears to be, in short, little we can do if we wish to judge one definition against another.

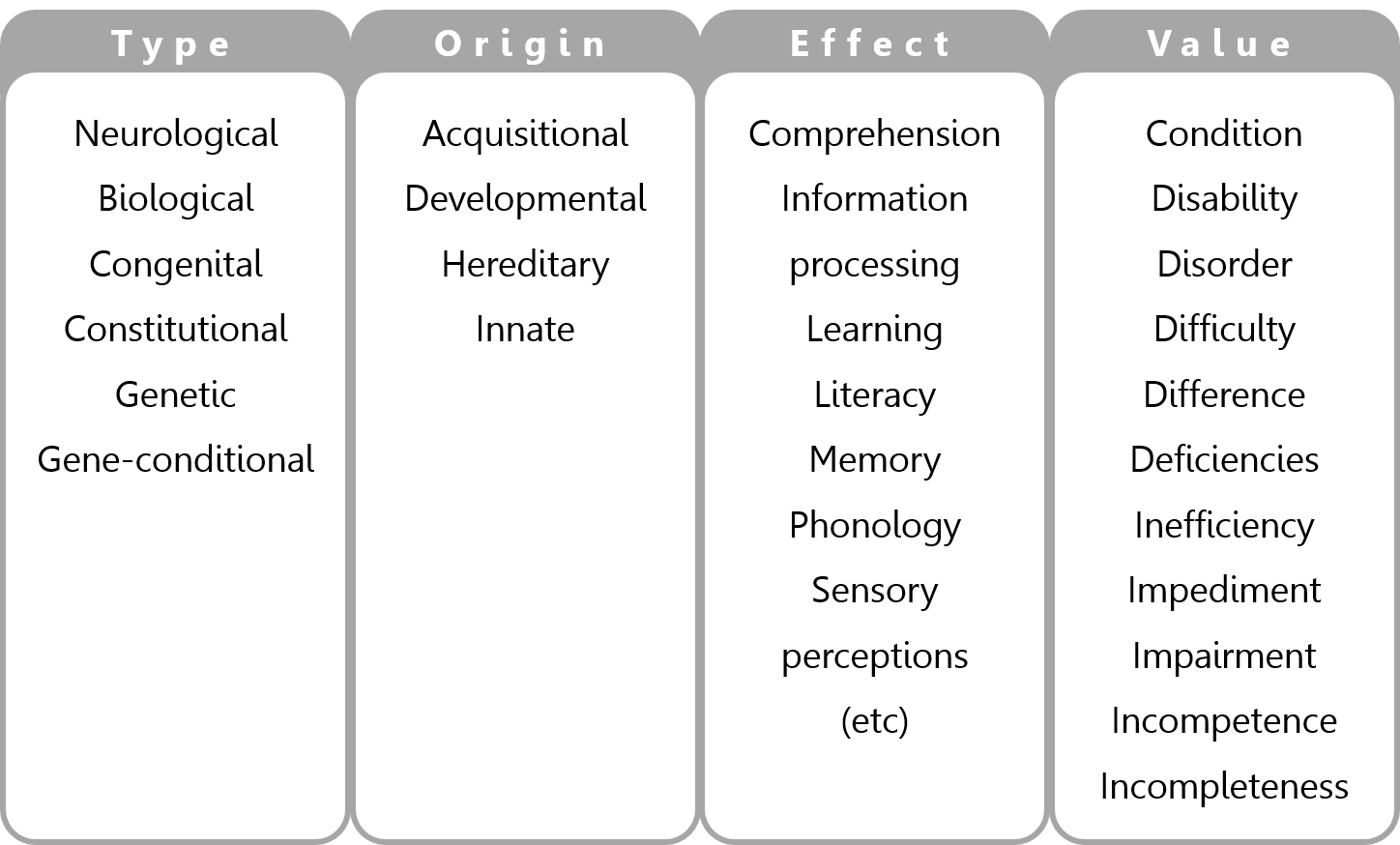

While the various definitions don’t all contradict each other, many of them do not sit comfortably with each other either. To show this, we can break down most definitions into four parts: the type, the origin, the effect, and the value. The type signifies whether it is seen as genetic, “constitutional”, etc. In other words, what sort of thing dyslexia is. The origin signifies how one comes to have dyslexia (Is it acquisitional? Is it hereditary?). The effect details the skills it affects. Finally the value shows how an organisation views dyslexia (often negatively). We have listed many of these types, origins, effects, and values, below.

The first thing we notice is that there is a fairly wide range of descriptors. We also notice that many organisations may share one of the categories (they might both say it is “neurological”), but not another (one may say dyslexia is “acquisitional”, another may say it is “innate”; one may say is affects “literacy” while another may say it affects “phonology”; one may claim it is a “disability” while another may say it is a “difficulty”). And perhaps most worryingly, we notice that in all but one of the value entries we have listed, people with dyslexia are labelled negatively: as disabled, disordered, inefficient, impaired, etc. And who is to say that this is wrong?

III. Conclusion

We are left with a difficult conclusion: if what we have said above is correct, then what’s to stop anybody from defining dyslexia however they please? It seems there is nothing. What universally-accepted standards do we have – could we possibly have – to say which definition is “wrong”? And without such standards, how can we ensure that people with dyslexia around the world will have their needs, and their safeguarding needs, adequately met?

If this seems extreme, consider the following challenge: in some cultures, dyslexia is considered to be a curse, or even a possession by evil spirits.²⁷ We may guess that the vast majority of those living in scientifically-minded countries would find this both shocking and absurd. But with no definitive definition to fall back on, we are left with very little but the operations of power dynamics – shouting down those we disagree with, excluding them from the conversation, ridiculing them as “not thinking like we do” – to show that they are wrong. And this seldom wins the argument if we are seeking to talk people out of mistreating their at-risk children. With so many competing definitions already in circulation, an alternative and horrific view such as that dyslexia is a curse, that reflects the culture of those defining it, may simply be recognised as “just one option among many”.

So we can put forward the claim: that with so many varied and disparate definitions of dyslexia, and without any neutral standard by which we can judge one as correct and another as incorrect, we are leaving vulnerable children at risk. And that is not at all uninteresting.

Al-Odaib, A. N., & Al-Sedairy, S. T. (2014). An overview of the Prince Salman Center for Disability Research scientific outcomes. Saudi medical journal, 35(Suppl 1), S75.

Boghossian, P. (2007). Fear of knowledge: Against relativism and constructivism. Clarendon Press.

Kargin, T., Guldenoglu, B. (2016). Learning Disabilities Research and Practice in Turkey. Learning Disabilities--A Contemporary Journal, 14(1).

Rose, S. J. (2009). Identifying and teaching children and young people with dyslexia and literacy difficulties: An independent report from Sir Jim Rose to the Secretary of State for Children, Schools and Families. Department for Children, Schools and Families.

Boghossian, P. A. (2006). Fear of Knowledge: Against Relativism and Constructivism. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, pp. 1-152.

Kargin, T., and Birkan G. (2016). "Learning disabilities research and practice in Turkey." Learning Disabilities: A Contemporary Journal, vol. 14, no. 1, spring 2016, pp. 71+. Gale Academic OneFile, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A452290872/AONE?u=anon~b5966d6b&sid=googleScholar&xid=285c22d1.

Al-Odaib AN, Al-Sedairy ST. (2014). An overview of the Prince Salman Center for Disability Research scientific outcomes. Saudi Med J. 2014 Dec;35 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S75-90. PMID: 25551118; PMCID: PMC4362095.

Rose, Jim, Department for Children, Schools and Families (DCSF), corp creator. (2009). Identifying and teaching children and young people with dyslexia and literacy difficulties : an independent report. Available under License Open Government Licence. Available under License Open Government Licence.

Snowling, M.J., and Hulme, C. (2012). Annual research review: the nature and classification of reading disorders--a commentary on proposals for DSM-5. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012 May;53(5):593-607. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02495.x. Epub 2011 Dec 5. PMID: 22141434; PMCID: PMC3492851.

Volkova, L. S. (Ed.). (2007). Логопедия [Logopedia]. Moskva: Vlados.

Footnotes

1 - https://dyslexiaassociation.org.au/dyslexia-in-australia/

2- https://www.dyslexiacanada.org/

3 - https://www.ordblindeforeningen.dk/viden-om/

4 - https://eda-info.eu/what-is-dyslexia/

5 - https://www.apedys.org/dyslexie-cause/

6 - https://www.bvl-legasthenie.de/legasthenie.html#content

7 - http://www.dyslex.hu/dyslexia.html

8 - https://www.dyslexiaindia.org.in/what-dyslexia.html

9 - http://www.mdamumbai.com/about-dyslexia.php

10 - https://dyslexia.ie/info-hub/about-dyslexia/what-is-dyslexia/

11 - https://www.npo-edge.jp/about/englishpage/

12 - The Japan Dyslexia Association, whose website (www.jdyslexia.com) is currently offline, had previously said of dyslexia that first, one has to use the word “disability”, because in the field of medicine, things that do not work are customarily described as disabilities. The word “disability” may however be a bad word, and it’s becoming increasingly common to write “gai” (damage, harm, barrier, injury…). However, as this historical definition is currently hard to verify, we may discount it in our present study.

13 - https://www.dyslexiakenya.org/what-is-dyslexia/

14 - https://www.dyslexiafoundation.org.ng/what-is-dyslexia/

15 - http://www.dislexie.org.ro/tulburarile-de-invatare/dislexia/

16 - See Volkova (2007), and https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ906433.pdf

17 - https://das.org.sg/learning_differently/understanding-dyslexia/

18 - https://www.bdadyslexia.org.uk/news/definition-of-dyslexia and https://www.bdadyslexia.org.uk/dyslexia/about-dyslexia/what-is-dyslexia

19 - https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200910/cmselect/cmsctech/44/44we16.htm

20 - See for instance https://www.bps.org.uk/psychologist/brief-history-dyslexia

21 - https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/BILLS-117hres1424ih/html/BILLS-117hres1424ih.htm

22 - https://dyslexiaida.org/definition-of-dyslexia/

23 - See Snowling & Hulme, 2012.

24 - https://www.american-dyslexia-association.org/Dyslexia.html

25 - https://improvingliteracy.org/brief/commonalities-across-definitions-dyslexia

26 - https://mgiep.unesco.org/article/about-dyslexia

27 - https://static1.squarespace.com/static/63204e7755fad958767f9eab/t/63346e9326e84e597ea26d5e/1664380565941/What-is-Witchcraft-Booklet-2017.pdf